Pleasant memories of my younger days, warmed by 15 years of nostalgia, led to Hanoi’s selection for a fall trip. With just over a week on the ground, Hannah and I opted to base ourselves in the long-running Vietnamese capital, a tireless yet pleasant city set along the curving floodplain of the Red River. Revisiting memories in a place like Vietnam is risky: the country is young, dynamic, quickly growing, quickly changing. Would it feel the same? A midday stroll around the Old Quarter quickly quieted my doubts. Shops and restaurants still line every street, t-shirts of questionable taste and massage parlours of questionable repute, a plethora of consumer goods and services. More skyscrapers stand, with more on the way as cranes dot the flat horizon. Each morning is a rising symphony of concrete breaking and stones cracking, a city being reshaped in real-time. Hanoi, to my delight, is as kinetic, engrossing, and plain lovely as before.

The Old Quarter, like the rest of the city, is a jumble of narrow, intersecting streets crossed in all directions by traffic. Motos – the apex species – swarm around the bulkier cars and buses, while trishaws, a tourist-only fixation operated by men in replica green pith helmets, plod along next to locals on bikes. Pedestrians move with determined aloofness along the street edge, pushed off the sidewalks by restaurant tables, café stools, meat grillers, shoe repairers, and produce sellers. The Old Quarter emerged, unsurprisingly, as a trading and market centre midway between the Red River and Thang Long, the imperial citadel and political centre to the west. Traditionally, each street within the Old Quarter was home to a specific trade (copper, silver, bamboo wares, etc.), with 36 streets in all, together ensconced behind long-gone walls. Today the only surviving gate to the Old Quarter is O Quan Chuong, continuing to serve its function as an entry from the river to the city.

The Old Quarter wraps around the upper half of Hoan Kiem Lake, the most iconic of the many small lakeside parks dotting Hanoi. Hoan Kiem, the “Lake of the Returned Sword”, is specifically important, the mythic location where Emperor Le Loi was gifted a magical sword by a golden turtle. With this sword, the emperor fended off the invading armies of Ming China before returning the sword to the lake – thus the namesake. This event is commemorated at Ngoc Son Temple, on a small island within the lake. Inside the temple, two purported giant turtle specimens are preserved and on view, though looking at these turtles, as long as I am tall, and the small size of the lake, I am skeptical. As a national myth however, it works, and an independent Vietnam was preserved for centuries until the 19th century arrival of the French.

The French established their colonial counterpart at the southern end of Hoan Kiem Lake, as Vietnam was annexed into the expanding empire and split into three parts – Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. This quarter of Hanoi follows the European design of the time, with straight, wide streets intersecting at strategic points where key buildings are sited. These buildings are easy to identify by their neoclassical architecture and buttery yellow colours. Elegant examples include the 1911 Opera House and the current Museum of the Vietnamese Revolution, appropriately coopted by the victorious Communists. The museum offers an exhaustive room-by-room march through the successful 20th century independence struggle. This complex and compelling story is inexplicably framed around letters, newspaper clippings, speeches, and various Party congresses, capped off with rooms of gifts presented to the Vietnamese government. This lifeless style saps the drama from a compelling, complex story, a seeming hallmark of Communist government exhibitions. Meanwhile, a new Coca-Cola vending machine in the hallway quietly suggests that the revolution has work to do.

Similarly staid, the National History Museum is another repurposed colonial building, this time the former Far East Institute. Its most interesting pieces were the enormous brass drums, well over a meter in diameter with intricate reliefs carved on all sides and dating back over 2,500 years. The Women’s Museum down the street, recently redone and housed in a Modernist building, features a succession of rooms guiding the visitor through the traditional world for women of the Kinh and many other ethnic groups found in Vietnam, with both day-to-day and ceremonial rites. The museum does not answer what the role of women in today’s Vietnam should be, though one of the more compelling media pieces was a looping video of women working as street vendors, balancing their wares, often fruit, vegetables, or flowers, on shoulder-poles. All of the women interviewed had left nearby villages for opportunity in Hanoi, working 12 or more hours a day while trying to give their children a better future. It is a touching, difficult set of interviews that speak to the grit and determination of Vietnamese women.

For all the yellow colonial buildings, the French quarter, like the rest of Hanoi, inevitably faces the future. One relic, the former Bank of Indochina, an austere Art Deco beauty visible from the lake, now, appropriately, houses the State Bank of Vietnam. While some women peddle on the sidewalks, others run restaurants. A favourite example for me, also with a woman running the show, was the decidedly globalized Wong Bar Wine, a low-ceilinged wine bar set down an otherwise empty alley. Small, with perhaps a dozen seats, the space is an enclosed world dedicated to wine and Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wai. Clips of his films play on the door, while the score from the subtle, tragic film In the Mood for Love plays. It is atmospheric and well-crafted, a suitable stage for the auteur and the wine.

A sharp shift in tone is found to the west around Ba Dinh Square, the expansive and mostly empty open space where the main function seems to be serving as foyer to the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum. This stark, squat Leninist-style structure was built to house the embalmed body of Uncle Ho, despite his express wishes to be cremated. Incongruently situated nearby is the One-Pillar Pagoda, a small, thousand-year old structure in the middle of a small pond, said to imitate a lotus blossom. In another sudden architectural lurch, the adjacent Ho Chi Minh Museum also tries to imitate a lotus, but with the subtle grace of Brutalist concrete. Inside, in an echo of the Joseph Stalin Museum in Georgia, one must ascend a processional set of stairs to marvel at a larger-than-life Ho Chi Minh. After paying respects, a visitor follows a loose narrative of his life, inevitably entwined with the 20th century wars fought in Vietnam, tinted in expressive, almost surreal set-pieces from the national leader’s life. It is a truly unique approach to education.

Ba Dinh Square sits atop centuries of accreting political power. The Presidential Palace is the former home of France’s Governor General of Indochina, one of several colonial era buildings (again, butter yellow hued) adapted to serve the Vietnamese state. Before the French takeover, the area was Thang Long, seat of Vietnamese ruling dynasties since the 11th century. The former citadel was mostly destroyed by the French, though some pre-colonial remnants remain like the Mirador Tower, which spies over the citadel wall along busy Dien Bien Phu Boulevard. At the northern end is Cua Bac, the one-time northern entry to Thang Long which is today a museum. Outside, women and couples stage themselves for photoshoots dressed in traditional ao dai, while enterprising locals rent out bicycles and flowers as ready props.

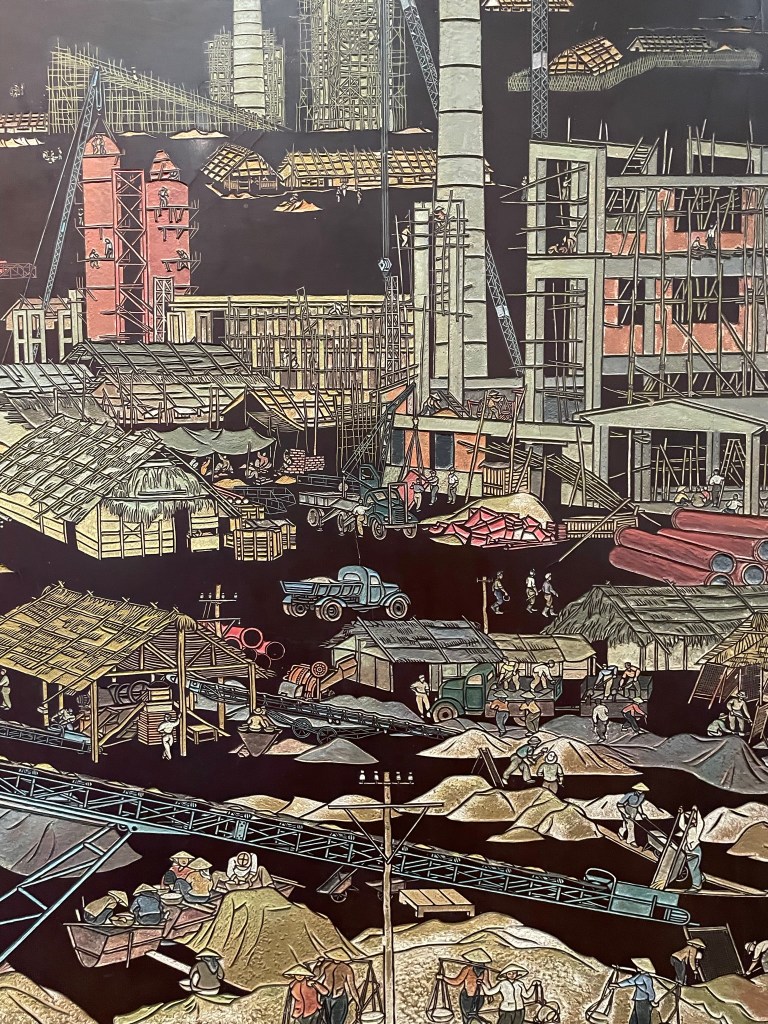

To the south is the Museum of Fine Arts, again in a reused neoclassical French building. Here is an admirable collection moving through the recent timeline of arts in Vietnam. The European influence is evident in the early 20th century with a sharp turn from landscapes and calligraphic scrolls to more experimental and avant garde styles. Unexpected but more interesting were the mid-century collection of lacquer paintings and engravings. These fused a traditional Vietnamese material into contemporary topics, focused strongly around three apparently enduring and politically acceptable themes: the struggle for Vietnamese independence, the timelessness of village life and traditions, and the bold, prosperous industrial future to come. The lacquer engravings are particularly complex and intricately detailed, many created in a time of grinding poverty during decades of war. The dedication is admirable and, like much here, an example of the local culture incorporating external influences into something distinctly Vietnamese.

While we loved Hanoi, we did manage to leave the city for a daytrip.