Along with our longer day trips, we traveled to many different areas in the city as well. Transportation is the life blood of any city, the key ingredient to it all functioning, and this is truer yet in a megacity like Mexico. Driving here appears to be an act of faith, enduring frustration punctuated by moments of relief where things actually go as planned. For shorter trips, we would just walk but for anything longer, if it was on the Mexico City Metro, that was almost always the fastest way around town. That is not, I’m sad to say, the most comfortable method. The metro is entering its golden years and it shows, with virtually no signage and absolutely nothing announcing which station you are at – a traveler must simply pay attention and be ready to push off the train, if needed. The underground, in contrast to the arid city above, is somehow humid and with little airflow. There are positives though, like the opportunities to upgrade one’s cell phone accessories, buy an ice cream, or enjoy an impromptu live metal concert. I cannot imagine any of these in Vancouver, and its our loss.

Another positive in Mexico City is the continued investment in new transportation. In the last decade, MetroBus has launched a network of dedicated bus lanes with sizable stations and sizable crowds. The drivers are well-trained, comfortably blasting their horns at jaywalking pedestrians. In the outer districts, a series of MexiCable cable cars float quietly over the tops of neighbourhoods, bypassing the roads altogether. Bike lanes, protected by aggressive speed humps, are everywhere and well-used. As a planner, I was of course happy, even if more of our longer trips ended up in an Uber, where we learned first hand that while cars must still stop at red lights, cyclists, motorcycles and police vehicles do not.

Uber was a good way to learn about the city, like the unwritten rules around who can skip traffic lights or that the Paseo de la Reforma, the central avenue of the megalopolis, is lined with statuary alternating between urns and busts, all framed by a growing canyon of skyscrapers. We learned how bold vendors fill the gaps during a standstill, wandering between cars with their wares or that chilango drivers are a mixture of grit and patience, oscillating between resignation and lead-footed ambition. We saw this firsthand with our Uber of the week, Ivan David and his Mini Cooper convertible, speeding blithely between any obstructions before aggressively braking for the better part of an hour. It made for a memorable, somewhat breathtaking ride through the city’s southern expanses before we alighted at the Anahuacalli Museum.

The museum is a stunning structure built of volcanic stone resting across a large square in a quiet section of Coyoacan, surrounded by a small remnant of high desert. Architect Juan O’Gorman’s building evokes pre-Columbian Mesoamerican religious structures, heavy stone and deep walls giving way to a darkened inner sanctum. The ground level is dim, representative of the underworld, and rising up successive levels gives way to the earth and then the sky above on a terrace facing out past the desert over the surrounding sprawl and the mountains cloaked in the ever-present haze of Mexico City. The building is carried off to stunning effect, its era hard to place, and its not quite like any place I’ve seen.

Anahuacalli opened in 1964 following over two decades of construction and the death of its patron, Diego Rivera, the same well-known muralist whose work adorns Mexico City’s public buildings. Here, Rivera’s sizable collection of pre-Columbian artifacts is on display in a varied series of chambers, including long sun-lit chambers, a soaring atrium, and crypt-like underground spaces. At the same time, the museum engages with contemporary artists, a pair of whom exhibited their work throughout the building in conversation with the old carvings, ceramics and statues. Rivera, not to be forgotten, has a number of mosaics embedded into the ceilings. The cumulative impact is mesmerizing and even daunting, an experience of a museum quite unlike any I’ve had the chance to experience before.

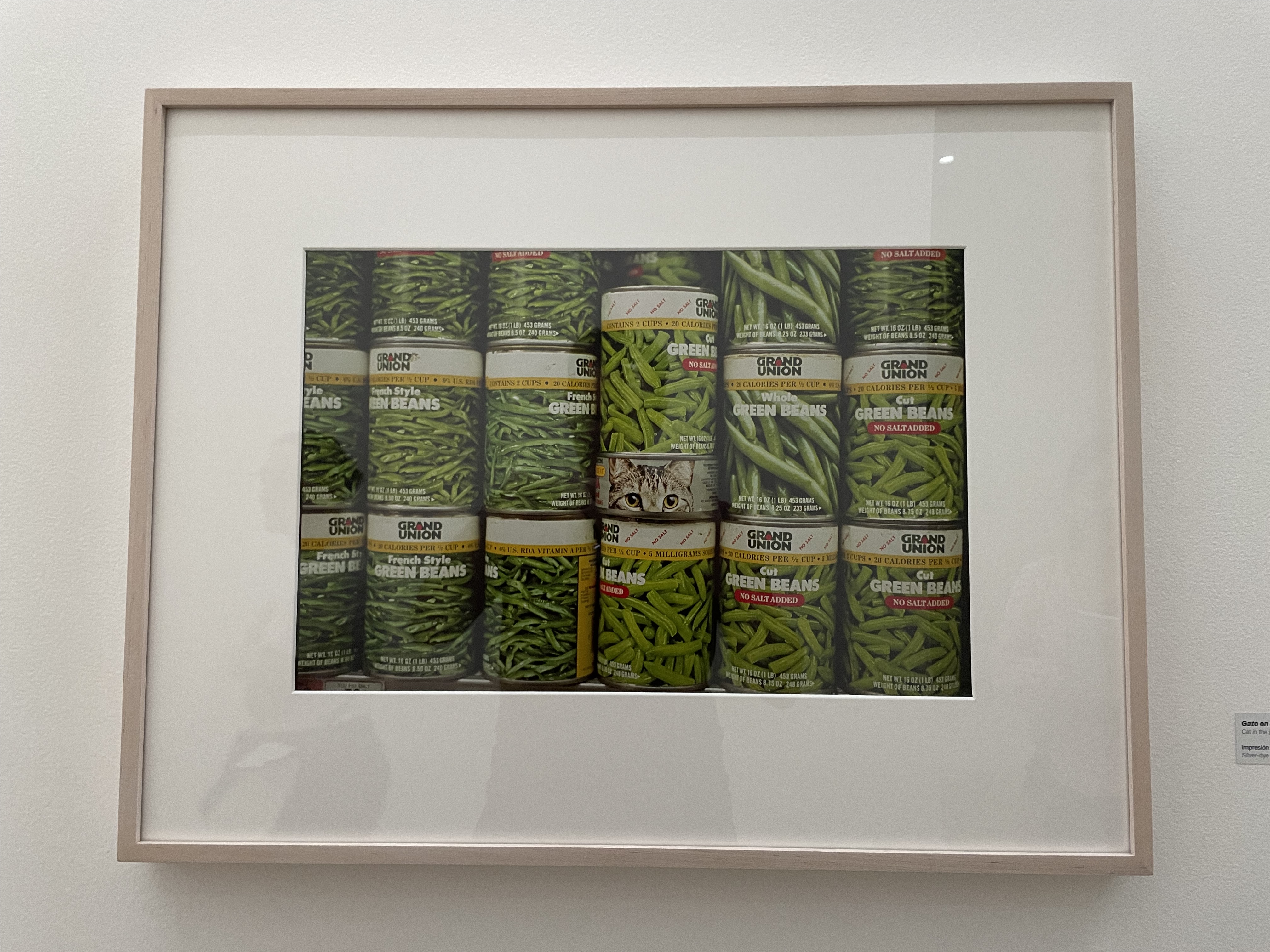

To the north in Polanco, we visited a pair of millionaire-funded legacy museums facing one another across a plaza. The first of these, Museo Jumex, has an elegant if understated design by David Chipperfield, fit for purpose with a rotating cast of exhibitions. There we saw a playful if somewhat dense (at least for me) exhibition by Gabriel Orozco, a contemporary Mexican artist. Across the street is the more dramatic Museo Soumaya, a twisting, reflective structure that seems to function as the art repository of Mexico’s richest man, Carlos Slim. While the exterior is stylish, the interior is a windowless spiral that escalates through successively tighter turns until arriving at the upper level, near the white steel rafters. The collection is undeniably impressive, but overcrowded. The central message appears to be that Mr. Slim has a lot of art, and it at times feels like we were simply wandering through his grandiose storage unit.

Post-Soumaya we wandered south through Polanco before plopping down at a sidewalk cafe to marshal our reserves to head onward to the Anthropology Museum. Here, the owner came out and chatted with us in excellent English. Upon finding out we were Canadian, he promptly disappeared before returning with a glass each of top-shelf mezcal and tequila – for sipping, he urged. They were both excellent, along with the warm hospitality. Fired with liquid courage, we tackled the sprawling Anthropology Museum, an overwhelming speed run through thousands of years of history in Mexico as told through a selection of its many different indigenous peoples, past and present. It remains a stellar collection, all-consuming and an ongoing test of the basic Spanish I’ve learned over the years, capped off by the grand hall serving as host to the Aztecs ruins.

While preserving the past, Mexico City also looks forward. In the early 21st century, the city undertook the Vasconceles Public Library, intended as an ‘ark of knowledge’. The structure is an elongated metal and glass rectangle with successive stacks rising up seven storeys within a central atrium. Centered on the ground floor is a large Gabriel Orozco sculpture of a whale skeleton. The building ran into numerous issues and cost overruns, but the finished product today is peaceful, calm, and even hopeful. I’m a big fan of investing in public architecture, even though it can go wrong, and Mexico City, for better and worse, has made the efforts over time.

On the private architecture side, a similarly stunning experience was our visit to Casa Gilardi, a residential building dating from the mid-1970s. The building is straight lines, natural light and simple forms, clean modernism with boldly coloured walls. A towering jacaranda tree, clinging to its last burst of purple flowers in the late spring, sits in the middle of the courtyard, the original design feature that the house wraps around. Casa Gilardi is a later work of Mexican modern architect Luis Barragan, built originally for a pair of bachelor architects and later becoming the family home to one of them. Our tour guide was a son who grew up here, and spoke lovingly of the house and its history. It was a stunning space, modest, warm and rich in character, a retreat from the hectic streets of Mexico City and a highlight of the trip.

Another, older example of domestic architecture, now public, is Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul in Coyoacan. The one-time home, now museum, is not a deep cut site. Tickets book out weeks in advance online and the line wraps around the corner where you wait for your entry time. Casa Azul admirably guides one through Frida’s life, though with too little of her art actually shown. Nevertheless, it is an interesting stopover and a sharp contrast to the Leon Trotsky Museum, where the exiled revolutionary lived in much more modest circumstances – Kahlo’s large, bright kitchen filled with art and tilework is a sharp contrast to the dim galley used by the Trotskys. Ultimately Leon’s stay in Mexico was cut short by a ice axe wielding assassin, a sign that the bricked up windows were a good investment yet not enough. The differing financial states continue today, and the Trotsky Museum is dated and a bit time-worn. There is no line-up outside the door.

Regardless of neighbourhood, Mexico City consistently boasted excellent food and drink at all price points. Hole-in-the-wall restaurants abound in the city, dishing up dollar tacos and generous tortas. Nicer restaurants show up with smart service and delicious plates – tuna tostadas at Contramar and, for me, the chile relleno at Masala y Maiz were favourites. I learned that I like horchata, especially a black horchata served with coffee in Condesa. One night in Roma Norte we sat ourselves at a small corner coffee shop, where the staff sang along quietly to an in-house DJ who shouted greetings at neighbours passing by and customers played fetch with a local dog.

And that was what we had time to fit in. Other areas that had been on our list – San Angel, Museo Tamayo and the Contemporary Art Museum, Xochimilco, riding a cable car, and the National Autonomous University Campus – will all have to wait until next time. And there will be a next time, Mexico City is too good to pass on a return visit.

As usual, a lovely read, Zak. As always, I miss glimpsing you and Hannah amidst the stunning scenery. That would greatly complement the intimacy of your narrative! Love, Dad