“Crazy driver” she said, her cab deftly swinging out to the right lane and surging ahead. My cabbie, a middle-aged bottle-blonde with lip fillers, had no need for a turn signal. She repeated this a dozen or so times on the way from the airport to my apartment in Bascarsija while we crossed the length of the city, a jumbled cross-section of histories. Sarajevo stretches along the Miljacka river valley, encircled by steep green mountains. This country and its capital saw the worst of events during the dissolution of Yugoslavia. It remains a sad irony that the same mix of Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Croats, and Orthodox Serbs that made Bosnia a “Yugoslavia in miniature” after half a century also made it a bitterly contested place in the early 1990s. Thirty years on, my arrival coincided with the end of a marathon, as sure a symbol of a stable middle-class society as any other. Time had marched on, though I would find that memories remained.

20 minutes and 20 euros later I alighted in Bascarsija, the commercial heart of 16th century Sarajevo and today the undisputed epicentre of its tourist trade. The roots here trace back to the expansionist Ottomans, who within a century after their conquest of Byzantine Constantinople had swept up through the Balkan peninsula until being turned back at the gates of Vienna. Bascarsija, taken from a Persian word for trade centre or square, was and is exactly that. It built out during the 1500s after the appointment of Gazi Husrev-beg, the governor whose vakuf (‘deed of endowment’) conferred the groundwork of Ottoman civilization: a souq, caravanserai, mosque, madrasa, and hammam, among other buildings. Filling in the spaces between were traders and craftsmen, clustering so that each street represented a specialization. This system has eroded today, and instead it is souvenir shops, cafes, and restaurants that are omnipresent through the busy lanes filled with tourists. Whatever the shortcomings of contemporary Bascarsija, it makes for a lovely starting point and haunt for a visitor.

It was in the Husrev-beg that I met Amir. He was the only other person there that late morning, prostrate in prayer on the carpet while I awkwardly tried to take pictures of the interior. Amir was chatty and I quickly learned that he had arrived that morning via overnight bus from Belgrade (not recommended, it turns out). From Morocco originally, he spent time living in Vancouver as well, another small world moment. We talked about Islam and some of the parallels with Christianity before parting ways, and I appreciated that he didn’t need to ask where my beliefs lay. While many old buildings remain in Sarajevo, some of the elements that made it stereotypically “oriental” to other Europeans have been lost. Ottoman era homes are on display but only in the National Museum, a hodgepodge of thematic sections complete with the dated but compelling displays of pinned insects and macabre still life displays of stuffed birds and mammals.

The National Museum buildings date back to the late 19th century, a relic of a 50-year interregnum where Bosnia fell under Austria-Hungary’s care and civic architecture took a decidedly Habsburg turn to stone and stucco. This period of rapid growth was rudely interrupted by World War I, which would prove to be the death knell for the tottering royal house after more than five centuries. The Great War began in Sarajevo, on an unassuming street corner where Gavrilo Princip, a teenaged South Slav nationalist, shot and killed the heir presumptive, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie. Here the Latin Bridge still spans the shallow Miljacka and a one-room museum marks the spot. Its collection claims to have the assassin’s weapon, a small and unassuming handgun. Nearby are mugshots of Princip and his co-conspirators, marked for history with a seemingly stunned expressions. Princip died in prison, a neglected young man who had lived long enough to see the destruction his actions precipitated.

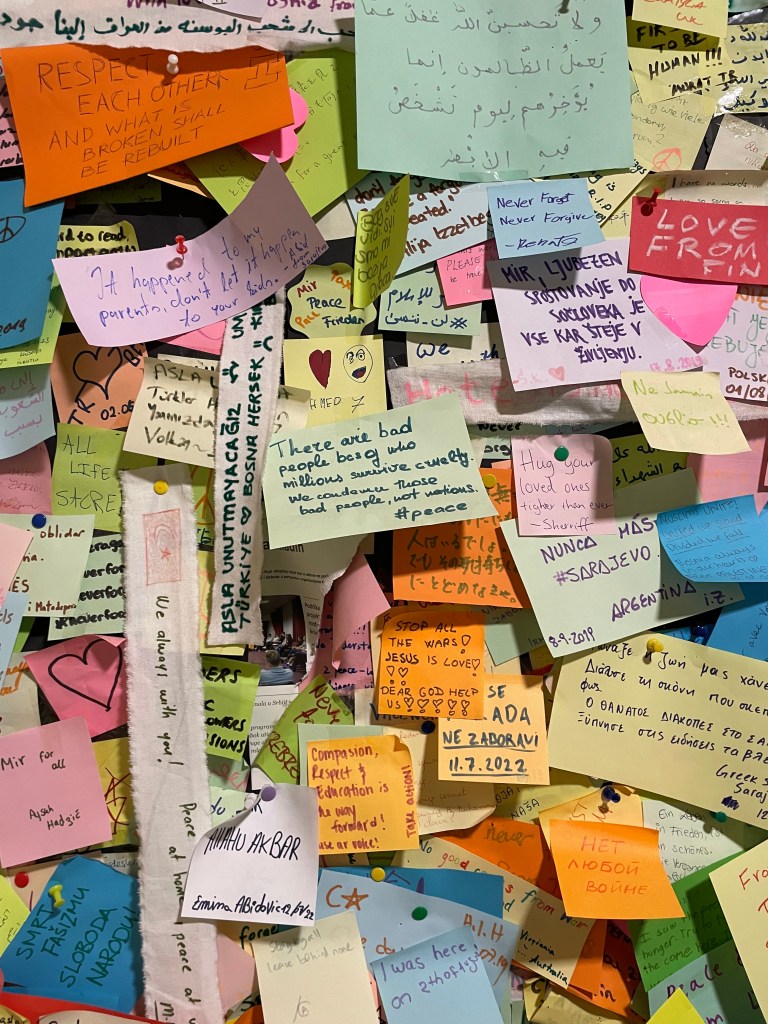

As in France, World War I was hardly the end of war, just the signal of new ways to wage it. There are a half dozen museums scattered around Sarajevo sharing different aspects of the Bosnian War of the 1990s. I visited those dedicated to genocide and the siege of Sarajevo. While the larger arc of the war and the 1425-day siege of Sarajevo by Serbian forces are described, the power is in the individual stories and artifacts left behind. A mother who donated her son’s sweater and fears his bones will not be found before she dies. A boy’s BMX bike, a gift, repurposed to haul water from aid stations. A care package of toys, some the same as those from my own daycare. While walking the street, you will come across the Sarajevo “rose”, red markings on the pavement marking where an artillery shell hit and killed civilians. The first rose I came across was in the Pijaca market, just after buying cherries, where 68 people died. Shells and snipers, set up on the surrounding hillsides, plagued Sarajevo residents. The day left me mired in sadness from these scars, as it should.

For a place so identified by recent tragedy, Sarajevo is still so much more. Its history over centuries is tangible and the contemporary, though very aware of the past, feels forward-facing. As a visitor, the city is small enough to be easy to manage, large enough to be interesting, and charming enough to stay longer. Unlike many European hotspots, you can still show up at sites or restaurants without any reservations. The yellow trams that ply the spine of the Sarajevo are like the city itself, alternately old or new, decrepit or sleek, and constantly on the move. For my last night I joined the scattered procession up to the fortress overlooking Bascarsija and down the length of the MIljacka valley. On the way down I stopped at a small bar, ordered a beer, and pulled out my book. Not long after dusk fell, the streetlights flipped on, and the last call of the muezzins rang out.