We spent the better part of a day carving a long arc over northern France, retracing our steps to Le Havre before turning east to Reims. The day’s drive ended in this mid-sized city of the Grand-Est region, which was chosen mostly for being in the right general location for our onward travels. I didn’t know what, if anything, to expect of Reims, but the first impressions were positive. Its city centre was well-populated, not too busy but lively all the same with locals participating in the outdoor café culture over coffees ahead of the seamless late afternoon transition to beer and wine. We walked a bit, both to get our bearings and to stretch our legs, coming across an old Roman arch and passing by the unassuming building where the Nazis surrendered to the Allis in May 1945. I was excited to see both the broad main pedestrian street and even more so the wireless trams gliding through. Ian, his patience honed by his own small children, humoured me while I talked about power transmission and took pictures of passing trams.

The highlight of Reims is its eponymous cathedral, a soaring affair rendered in the Gothic style and immediately reminiscent of the more famous Notre Dame in Paris. Seeing it as an architectural cousin to its counterpart in the capital though diminishes the Reims cathedral. Its site was where Clovis I was crowned king over united Frankish tribes in the 5th century, setting in motion many centuries of French monarchs up until the 1789 French Revolution, plus a few more bonus kings in the 19th century before France fully shifted to a republic. Many of those monarchs, most notably the Sun King Louis XIV and the considerably less lucky Louis XVI, were crowned in the Reims Cathedral. In a nod to this history and the 900+ year old cathedral representing it, we went for a proper French meal that night.

Leaving Reims the next morning, we made our way farther east to the battlefields of Verdun, driving past the appropriately named town of Regret, which seems to beg for a photo opportunity. In my haste I continued without stopping, though have had second thoughts since. Our sightseeing began atop the high point of the area, occupied since the 1870s by the Douaumont Fortress. This hulking stone structure was borne in the aftermath of the embarrassing French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent loss of Alsace-Lorraine, a national wound that would be a rallying cause half a century later. The fortress was largely obsolescent by the time it saw action again in World War I, a victim to accelerating technology that transformed modern warfare. Today the fortress is open for business and its damp stone interior is busy growing stalactites. Numerous corridors and stairs, with blocked entries, face onto unlit spaces. One such part of the fortress became the final resting place for hundreds of German soldiers killed by a massive munitions explosion and subsequently sealed off. It is a sad irony that this accident, rather than some assault, was the deadliest event at Douaumont.

Leaving the fortress, I was left squinting in the sun as we climbed atop it. Here the landscape is pocked with craters, some up to 30 feet in diameter, testifying to the physical durability of Douaumont, a target for both sides as it changed hands during the war. Also on the hilltop are various concrete and rebar structures capped with gun emplacements or observation slits. In some cases, the larger guns were raised from the depths below by hand cranks before they could reign havoc down on huddled doughboys. Some trenches remain, rebuilt or left to decay, and are still visible criss-crossing the area below the fort, another reminder of the Great War’s many wasted lives.

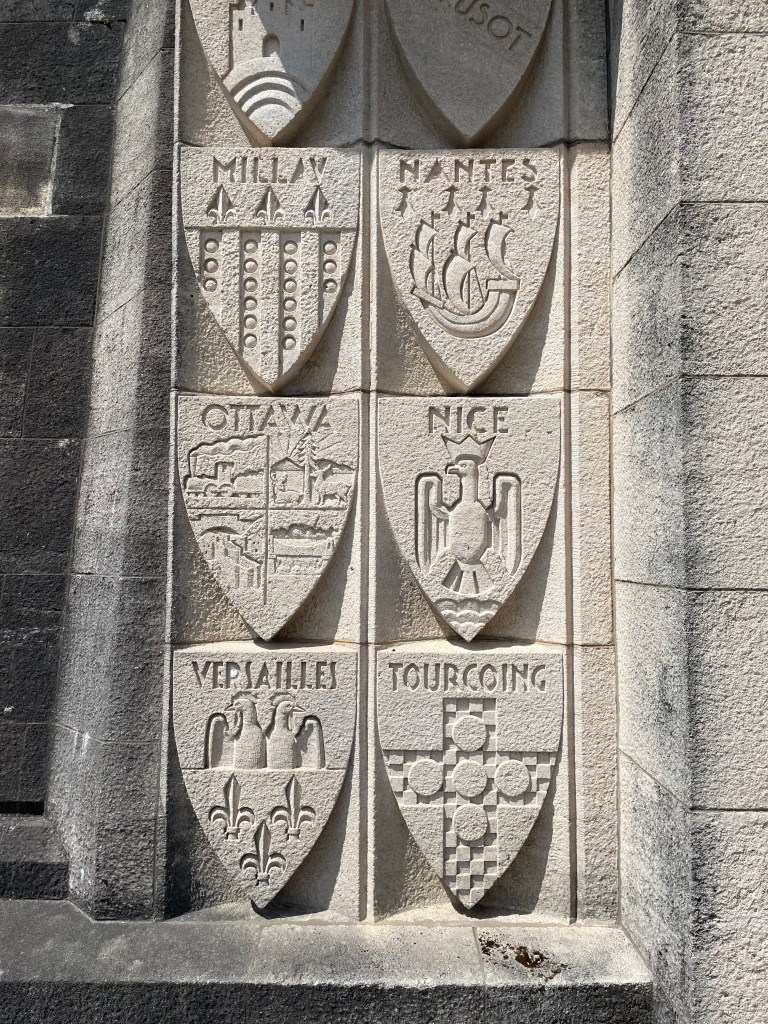

A short way down the road from the fortress is the Douaumont Ossuary, a stunning stone Art Deco monument situated on a promontory over more rows of headstones. The Ossuary was a direct result of the carnage of World War I, a statement by France and her veterans in remembrance of their losses in the hope that such tragedies would not happen again. For the better part of a decade, construction and fundraising was carried out until the Ossuary’s official opening in 1932. The main hall runs the length of the structure, bathed in a deep orange light that adds to the solemnity of the space. From here, visitors can climb up the steps to the top of the tower for a view over cemetery and the surrounding countryside of Verdun, where so many of these men lost their lives.

One particularly haunting aspect of the Douaumont Ossuary is in the name itself: the building houses the bones of over 130,000 soldiers who fell at Verdun. Ringing the ground level of the ossuary are small windows, each peering into a chamber, and each chamber piled with bones. It is chilling to look into these in turn, the last remains and resting places of so many broken men. Ultimately it is a dual space, one both horrifying and peaceful, and there is added poignancy that the intent of the ossuary, the idea of creating this space to express grief and say never again, is so far removed from most lists of places to visit in the country. This sadness cuts deeper when you recall that it was only a year after its opening that Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, setting in motion a new and inhumane chain of events. We left Douaumont under an emotional cloud that we only shook as we traveled further from these grounds, down winding rural roads past farms and forests, and onward into Belgium.