The last stop of the trip was Bologna, the capital of Emilia-Romagna. For this leg, we had an AirBnB booked, a great choice as it includes all the finer things in life: a couch, a fridge, stovetop, and even a washing machine (but no dryer). That final item was extremely welcome at this stage, especially with the scorching weather we’d been experiencing. Bologna was meant to be more relaxing, a less intense location than Venice where we could take advantage of the slower pace and the glowing food reputation of the city and region. Multiple people told us it was hard to get a bad meal in the city, and we put that to the test on the first night, stopping into a trattoria across the street. Shortly after placing our order, the proprietor appeared at a neighbouring table with a warm risotto which he stirred in the hollow of a wheel of parmesan. This was a delicious-looking omen for our imminent meal, and for Bologna as a whole.

As a city, Bologna has much to recommend itself to the visitor, but receives nowhere near the tourist trade of Florence, Venice or Milan, all short train rides away. It’s centre dates back hundreds of years and is an enjoyable juxtaposition of warm pastel buildings squared with shutters and patios, and home to a namesake university which purports to be the oldest still operating in the world. Piazza Maggiore, in the core of Bologna, is framed by the usual assortment of important buildings and apparently in summer hosts movie screenings on the square. There is also a fountain graced by Neptune, an odd choice for a city that is neither a port, nor even on a river. The square is home to Bologna’s signature generational project and main church, the Basilica San Petronio, which began construction in 1390 and was finally consecrated in 1954. It’s exterior is unfinished, clad in brick and lacks the ostentatiousness of Milan’s Duomo or Venice’s San Marco. It is instead a curious church, the interior galleries flanked on both sides by a series of bespoke chapels, each seemingly designed without paying heed to the others, making for a curious mishmash of finishes all side-by-side. Adding to the effect is a 17th century addition for the benefit of Giovanni Cassini of a literal hole in the ceiling and complementary meridian line grafted at a diagonal across the church floor. While I’m sure there are stories of how this came to be, and the ensuing astronomical discoveries from Cassini as a result, I don’t know them. My focus instead was astrological and we hunted down our respective zodiac signs, successfully.

One of the medieval legacies of cities in the region, including Bologna, are the towers put up by well-to-do families to demonstrate their wealth and influence. The most renowned of these proto-skyscrapers are a pair known, creatively, as the Two Towers. The smaller tower is not open to tourists due to safety concerns: it leans at a greater angle than the renowned tower in Pisa and was emasculated with a height reduction over the centuries to accommodate this peculiarity. The taller of the two towers remains and for a small fee, you can climb up the vertigo-inducing staircases to over 300 feet above the city. For this stifling, humid climb a visitor is provided relief only through a few seemingly random openings where merciful cool gusts of wind blow in. At the top, this is supplemented by a full-blown breeze and a view of the red roofs of Bologna, and the Apennine foothills to the west. I tried not to dwell on the stability of this nearly-century old brick tower, trusting instead that if its stood this long, it will last a few more hours, at least. Instead I lingered atop for a bit, enjoying the rare combination of shade and breeze, before heading back down to earth.

The next day, an early morning train spirited us and some weary commuters off to Parma, about an hour away. The distance between the two cities is small, almost the same as that between Vancouver and Bellingham, but the two Italian cities are connected in an hour or less by 35 trains a day. Meanwhile, in the Pacific Northwest, we are still waiting the return of two slow daily trains. It is a jarring and absurd contrast. Ready for us in Parma was a small chartered bus, taking me, Hannah and a few other pairs of tourists on a three-fold food production tour. First stop: parmigiano reggiano (distinctly not parmesan cheese) in a family-run factory where the tour guide’s adolescent son spends his summer learning the family trade. We witnessed the morning mixing of milk and curds, the first stages of a process that lasts at least a year. For each 100 pound wheel of aspiring cheese, the moment of truth comes when the roving quality control inspector teams make their quarterly visit, tapping the wheel with a light hammer, listening for the right sound. This is the difference between placing an official stamp on the rind or shaving it off, the ultimate shame for the cheesemaker. The stakes are high, the aging process lasts 1-3 years and the failed cheeses sell for a tenth the price.

Stop number two was after a long, winding trip through the countryside past the urban limits of Parma, punctuated with a quick side of the road photo op of a random castle on a hilltop, which apparently is what passes for mundane here. The American equivalent is a roadside Howard Johnson’s. All this was en route to the prosciutto di parma factory, another family-owned affair in a picturesque setting. Once we were all properly covered in head-to-toe blue gowns, the enthusiastic guide literally walked us through a yearlong process in about an hour, a series of climate-controlled rooms mimicking the seasons where the pork legs cure after salting. Like parmigiano reggiano, there is an arcane quality control measure at the end consisting of a specialized horse bone tool being poked into each leg and sniffed. If the leg fails, it is consigned to life as some sad deli meat. Our last stop was a balsamic vinegar side gig at a vineyard, where time is the main ingredient as the grape must mixture reduces over the course of twenty years, a process making both parmigiano and prosciutto speedy by comparison. Slow food is alive and well here.

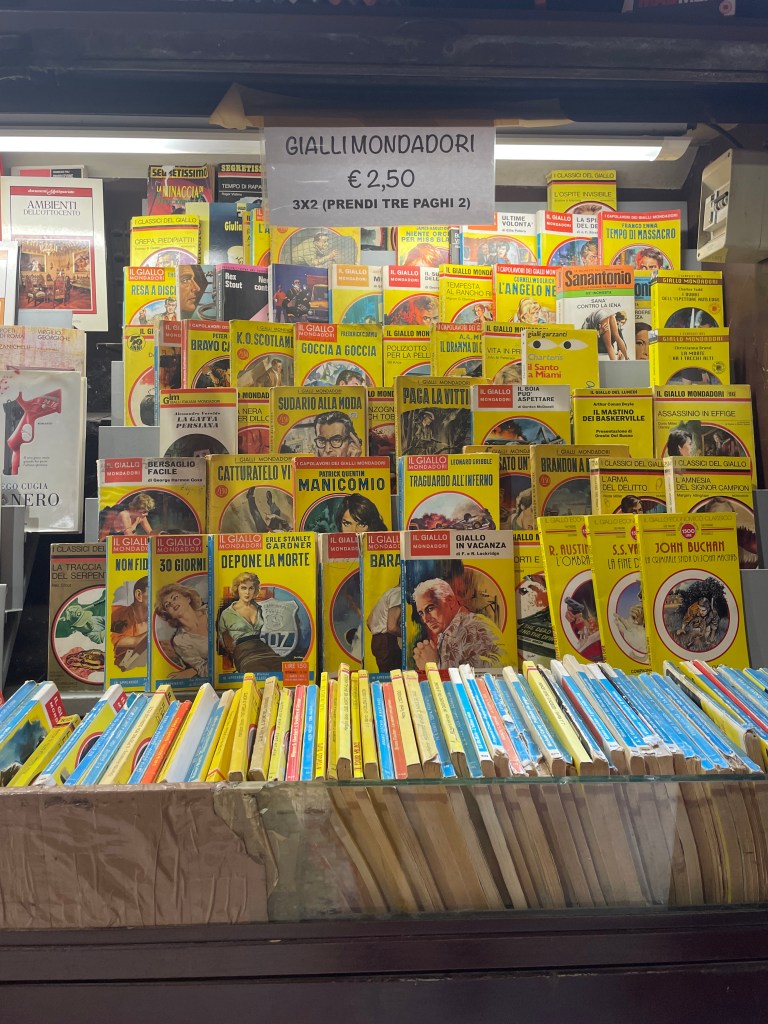

Our final day was informed by recommendations from our fellow food excursionists. Bologna’s old town is most distinct for its series of covered arcades spanning block after block, a hallmark of the cityscape that I’d never heard of before arriving. On top of the sheer volume, Bologna is also host to the world’s longest continuous arcade, a nearly four kilometer stretch starting in the city and winding steeply up a hill to the Santuario della Beata Vergine di San Luca (for brevity: the Santuario). It’s original objective was to keep the church icons dry during processions, but today it is the haunt of tourists and exercising locals willing to tackle the stairs and slopes. The top affords the typically exquisite house of worship and a complementary view of the city and country surrounding.

The other recommendation we followed found us in an office park on the outskirts of town, home to a local spa. Armed with our summer reading, we indulged in a process of cooling of with a quick swim, followed by a sauna or steam room before laying out in the deck chairs. The afternoon was a repetition of this pattern, broken only for a quick meal and spritz, before tending to the sad task of packing our things and preparing for our departure the next morning. After three years at home, it was incredible and invigorating to hit the road again for three weeks. I’m already thinking about what comes next.